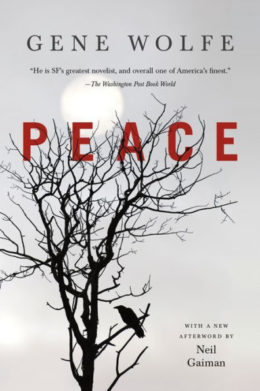

If Gene Wolfe is oftentimes a writer hard to decipher, there is nothing unclear or equivocal about his allegiance to the genre. He is first and foremost a writer of science fiction and fantasy, and in this he was always straightforward.

But there are a few cases in his body of work when the reader is not that sure of what genre (if any) a particular narrative is part of. That seems the case with Peace.

Attention: spoilers.

Published in 1975, this novel is a narrative related to us by Alden Dennis Weer, an old, rich man who’s apparently suffered a stroke and is starting to confuse past and present, recalling from memory incidents of his childhood and adolescence through his later life.

Seems pretty simple, right?

We should know better by now.

Maybe Weer had a stroke, or a heart attack. In the beginning, he consults a doctor and talks about his difficulties with standing up and walking. At the same time, though, he seems to be catapulted into the past, where he is seeing another doctor as a child. It is to this particular doctor that he attempts to describe what has just happened to him:

“…and I explain that I am living at a time when he and all the rest are dead, and that I have had a stroke and need his help.”

Evidently, the doctor of his childhood can’t do anything but be disturbed by the eloquence of the child.

Then Weer launches on a trip down memory lane, and the novel starts to shape itself into a quasi-pastoral description of early 20th Americana, something reminiscent (at least to me) of Ray Bradbury. The description of the house, the garden, and all the small details transport Weer to his childhood, a time of wonder… a time to which he seems to be irrevocably attached. He considers the garden “the core and root of the real world, to which all this America is only a miniature in a locket in a forgotten drawer.” And then he asks: “Why do we love this forlorn land at the edge of everywhere?”—“we” being only him, and “the edge” not only geographical in nature, but perhaps even the edge of life itself.

The first half of the novel comprises his memories of early childhood, complete with his mom, aunts, grandfather, and of adolescence, during which Weer is now living with his aunt Olivia (with whom he stayed for years while his parents traveled all over Europe; at first I thought that was a metaphorical explanation and they would be dead all the time, but near the end of the book he tells us that they eventually returned to America) and her three suitors.

The second half deals with adulthood and love, more specifically with Margaret Lorn, who he met as a boy, and a librarian—a woman whose name Weer can’t remember, something that upsets him very much, because, as he himself claims, “I who pride myself upon remembering everything.” This total capacity for remembrance, of course, does not belong to the young Weer, but to the old man, the narrator himself.

If the first half of the book is filled with Proust-like remembrances, the second is more diverse in terms of its literary influences. There are at least two tales inside the primary tale here: the story of the Chinese officer (which is told in a manner not-unlike that of Jorge Luis Borges) and the personal narrative of one of the characters, Julius Smart, a friend of one of Aunt Olivia’s suitors (and the man who will end up marrying her, in the end). Both tales share a common trait: They both deal with dreams, or at the very least have a dream-like quality.

In the story of the Chinese officer, a young man is summoned to Peking in order to pay his late father’s debt but is very worried because he has no money. During the trip, he spends the night in a hostel where he finds an old, wise man who lends him a magic pillow that can fulfill all his wishes. The young man sleeps upon the pillow that night; when he wakes up the following day, the old man is not there anymore. Then he travels on to Peking, and, although he has to work very hard, he finds out that all his dreams are becoming real. He becomes a rich man, married to four women, and lives forty years of happiness and tranquility. One day, however, when sheltering from bad weather in a cave, he meets the old man again, and the officer says that all he wants is to relive that one day when he first went to Peking. Angered by the ingratitude of the officer, the old man picks up his tea kettle and throws the boiling contents in the officer’s face; running away from the cave he finds that somehow the forty years of success never happened, and he is still the young man at the hostel.

The other story concerns Julius Smart, who, after getting a diploma in pharmacy, goes South to find work and meets Mr. Tilly, a strange man who owns a drugstore and gives him a job. But Mr. Tilly suffers from a very peculiar disease, a malady that is turning his body into stone. Smart will be introduced to a host of characters belonging to a circus, all of them malformed or disabled in some way. (This, by the way, seems to be another particularity of Wolfe’s work: Many of his characters are physically or mentally challenged in one way or another. What does this mean? How should these perceived imperfections, this recurring sense of loss or lack, be interpreted?)

Even Weer lacks something, and that something is life. From the moment the narrative begins, he is running on borrowed time, having suffered a stroke. We follow him through his memory-driven investigation of sorts and wonder what, exactly, Weer is going through. The science fiction fan might soon construct her own genre-specific theory, such as time travel via consciousness alone. Or maybe the reader will settle on a more outrageous supposition, like the one Weer implies when talking to the librarian:

“But I’ve felt I was no one for a long time now.”

“Maybe being the last of the Weers has something to do with it.”

“I think being the last human being is more important. Have you ever wondered how the last dinosaur felt? Or the last passenger pigeon?”

“Are you the last human being? I hadn’t noticed.”

He might be.

The other, maybe more obvious, explanation is that Weer is simply dead.

Buy the Book

Peace

An interesting thing is the use of a house as a sort of haunting place, a point in space for a dead person who uses it as a mnemonic device, revisiting his life. Wolfe has employed this at least once since Peace: In the anthology Afterlives, edited by Pamela Sargent and Ian Watson (1986), there is a short story written by Wolfe called “Checking Out.” It’s a very straightforward, rather simple story: a man who wakes up in a hotel room but has no idea of how he ended up there. While he is figuring things out, his wife is mourning him. When, after a while, he picks up the phone and tries to talk to her, she receives his call, but all she can get from the other side is noise. I’m not sure if there are further stories using the motif of the haunted house in similar ways in Wolfe’s work, but I’m surely going to investigate it further as we continue with the reread…

On this reread of Peace, the beginning of the narrative reminded me of the film Russian Ark, directed by Alexander Sokurov in 2002. Russian Ark begins in what seems to be a much more confusing way, but in essence what happens can be interpreted like this: A man (whose perspective is the camera’s, so we never see his face; only his voice is heard) apparently faints and immediately wakes up at the entrance of the old Russian Winter Palace in Saint Petersburg. Nobody seems to see him, except for one person: a man dressed in early 19th-century attire who seems to be waiting for him and urges the man to follow him inside the palace. From here, they will roam the building, crossing its rooms and different time zones, from the 18th century and Catherine the Great’s reign to the early 21st century, when the building has become the Hermitage museum—but also to early Soviet times and the dark days of World War II, when the city (then called Leningrad) was nearly burned to the ground in order to stall the Nazi troops.

While Wolfe of course couldn’t have possibly watched Sokurov’s film before writing his novel (though maybe Sokurov might have read Peace?), he certainly read Bradbury’s novels, many of which are filled with another element that’s very much present throughout Wolfe’s stories: nostalgia.

Maybe Weer is really dead. After all, Gene Wolfe says it himself in an interview for the MIT Technology Review in 2014. Or maybe he is the last man on Earth. Or—and this is my personal belief (“belief” because it occurs to me now that one possible approach to understanding Gene Wolfe’s stories is faith; we must have faith in them, instead of searching for definitive, concrete understanding)—maybe Weer is just an emanation, an echo of long-lost humankind, full not of sound and fury, but of sadness and serenity—or peace—told by a dead man. But we are never really sure, are we? In that same interview, also Wolfe says that all his narrators are unreliable. And that is always significant in his stories.

See you all on Thursday, July 25th, for a discussion of The Devil in a Forest…

Fabio Fernandes started writing in English experimentally in the ‘90s, but only began to publish in this language in 2008, reviewing magazines and books for The Fix, edited by the late lamented Eugie Foster. He’s also written articles and reviews for a number of sites and magazines, including Fantasy Book Critic, Tor.com, The World SF Blog, Strange Horizons, and SF Signal. He’s published short stories in Everyday Weirdness, Kaleidotrope, Perihelion, and the anthologies Steampunk II, The Apex Book of World SF: Vol. 2, Stories for Chip, and POC Destroy Science Fiction. In 2013, Fernandes co-edited with Djibrilal-Ayad the postcolonial original anthology We See a Different Frontier. He’s translated several science fiction and fantasy books from English to Brazilian Portuguese, such as Foundation, 2001, Neuromancer, and Ancillary Justice. In 2018, he translated to English the Brazilian anthology Solarpunk (ed. by Gerson Lodi-Ribeiro) for World Weaver Press. Fabio Fernandes is a graduate of Clarion West, class of 2013.